Māori Navigators: Ancient Seafaring Skills – Polynesian

admin

- 0

littlecellist.com – The Māori people of Aotearoa (New Zealand) are renowned for their remarkable seafaring skills, which allowed them to navigate vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean long before the arrival of Europeans. These navigational abilities are rooted in a deep knowledge of the stars, ocean currents, weather patterns, and the natural world, and they played a crucial role in the settlement of Aotearoa by the Māori ancestors. Māori navigators, known as tohunga rākau or tohunga whaiao, were skilled in using traditional methods passed down through generations to guide their waka (canoes) across the open sea.

This article explores the ancient seafaring skills of the Māori, their Polynesian roots, and the significance of navigation in Māori culture. It also highlights how these skills have been preserved and revived in modern times, linking Māori navigators to their Polynesian heritage.

The Polynesian Connection

The Māori people are part of the wider Polynesian triangle, which includes the islands of New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island. Polynesians are considered to be among the greatest navigators in the world, and the migration of Māori ancestors from the Society Islands (modern-day French Polynesia) to Aotearoa is part of a long tradition of seafaring and exploration that spans thousands of years.

The ancestors of the Māori are believed to have arrived in New Zealand in canoes from the eastern Pacific, around the 13th century. These voyagers were skilled navigators who used advanced techniques to travel vast distances across the ocean. Their migration patterns were not random; they followed carefully mapped routes based on an intimate understanding of the stars, winds, ocean swells, and the natural environment. This mastery of navigation allowed them to journey from one island to another, linking the Polynesian islands through a network of sea routes.

Traditional Navigation Methods

Māori navigators relied on a combination of environmental cues and oral traditions to guide their voyages. Unlike modern navigators who use instruments like compasses and GPS systems, Māori navigators had no written maps, yet they possessed an extraordinary ability to navigate across thousands of miles of open sea.

Celestial Navigation

One of the primary tools for Māori navigation was the stars. Polynesian navigators, including the Māori, were trained to read the night sky, using constellations, star paths, and the position of the sun to determine their direction. The stars Matariki (the Pleiades), for example, held great significance in Māori culture and served as a guide for seasonal and navigational purposes. Each star and constellation had specific meanings, and the rising and setting of certain stars indicated the time of year and the direction of travel.

Ocean Swells and Winds

Māori navigators also studied ocean swells, winds, and tides. They knew how to read the movement of the waves, which would tell them where they were in relation to the land. By observing the direction of the swells and how they interacted with the coastlines, they could identify their location even when they could not see the land. This knowledge was passed down through generations, allowing voyagers to confidently journey across the Pacific Ocean without the need for visible landmarks.

The Waka and its Role in Navigation

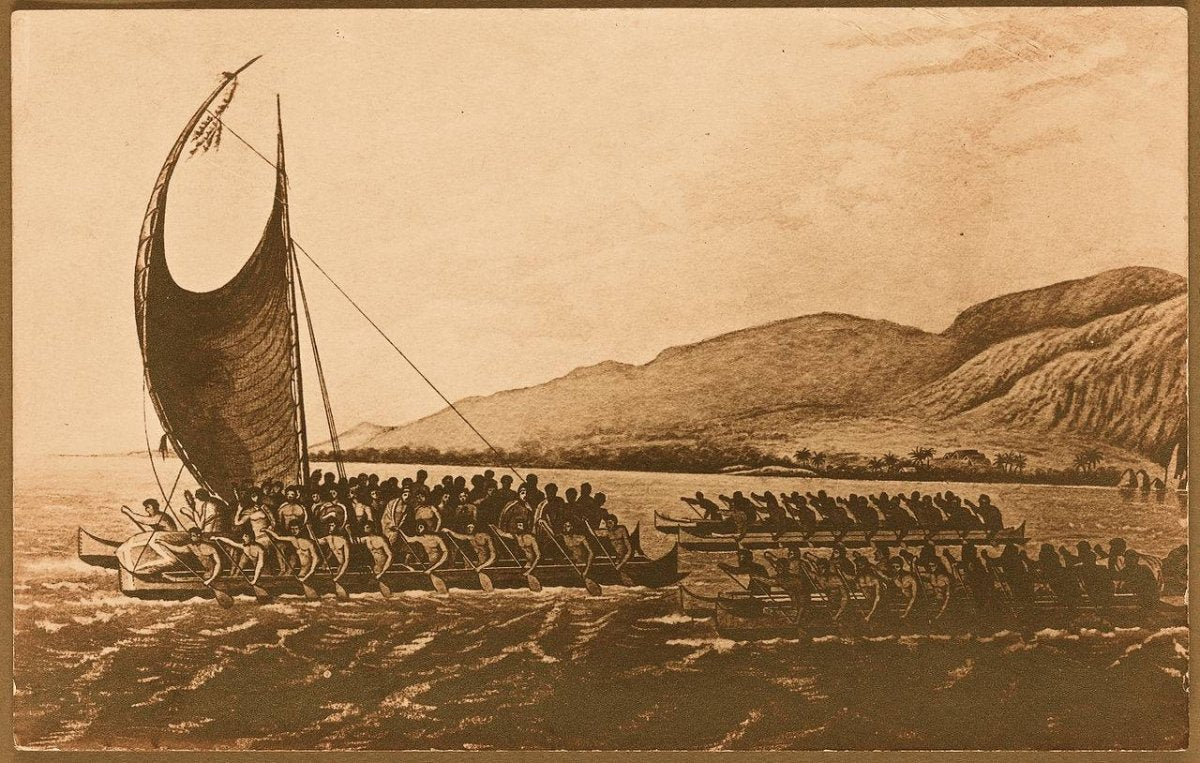

The waka, or canoe, was the primary vessel used by Māori navigators. These canoes were often large, double-hulled boats capable of carrying entire communities, and they were expertly crafted to handle the challenges of open-ocean travel. The design of the waka, its sails, and the skill of the crew were all integral to the success of long voyages. Crew members were responsible for maintaining the ship, steering, and coordinating the navigation based on the instructions of the tohunga or expert navigators.

The waka hourua (double-hulled canoe) was a particularly significant innovation, providing stability and speed on long ocean journeys. This vessel was specifically designed to withstand the turbulent seas of the Pacific and was essential for the successful migration of Polynesian peoples across vast distances.

Māori Oral Traditions and the Passing of Knowledge

The knowledge of navigation was passed down orally from one generation to the next. Māori navigators were taught by experienced mentors, often through stories, songs, and practical voyages. These traditions were deeply embedded in Māori culture, and the ability to navigate was seen as a sacred skill tied to the spiritual realm.

Each tribe or iwi (tribe) would have its own tohunga rākau (expert navigators) who were responsible for training the next generation. The knowledge was not just about physical navigation but also about the spiritual connection to the ancestors and the land. Many of the key navigators, such as Tama-nui-te-ra (the sun), were considered to have divine or semi-divine status, and their journey was seen as both a physical and spiritual quest.

One of the most famous Māori navigators was Rākaihautū, an ancestor of the Ngāi Tahu iwi, who is said to have led the first Māori voyaging expedition to Aotearoa. His journeys are recounted in numerous Māori myths and stories, preserving the tradition of Māori navigation for future generations.

The Decline of Traditional Navigation and the Revival

With the arrival of European settlers and the introduction of modern technology, the traditional skills of Māori navigation began to fade. The use of European-style ships, maps, and compasses reduced the reliance on traditional methods. Additionally, the colonization of New Zealand and the suppression of Māori culture and language contributed to a decline in the transmission of traditional navigation knowledge.

However, in recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in Māori and Polynesian navigation, as Māori communities work to reclaim and revitalize their cultural heritage. This revival has been facilitated by a growing movement to reconnect with ancestral knowledge and practices. Modern Māori navigators, like those involved in the Hōkūle‘a and Te Aurere voyaging projects, have sought to revive traditional methods by retraining in celestial navigation, ocean swells, and other key aspects of Māori navigation.

The successful voyages of the Te Aurere, a traditional Māori waka, in the 1990s and early 2000s demonstrated that traditional Māori navigation techniques could still be applied successfully in modern times. These efforts not only serve to preserve Māori cultural practices but also reinforce the deep spiritual and historical connections between Māori people and their Polynesian ancestors.

The Significance of Māori Navigation in Contemporary Society

The art of Māori navigation is not just a historical curiosity—it has deep relevance in today’s world. The revival of these ancient skills is an important step toward the cultural revitalization of Māori people, allowing them to reconnect with their ancestral roots and take pride in their heritage. The skills involved in traditional navigation also emphasize sustainability and a deep respect for the environment, which are values that resonate strongly with modern environmental movements.

Furthermore, the revival of Māori navigation reinforces the concept of whakapapa (genealogy), the interconnectedness of all things, and the ability to understand and respect the natural world. By returning to these ancient practices, Māori navigators are asserting their autonomy, sovereignty, and resilience, reinforcing their ongoing relationship with the land and the sea.

Conclusion

Māori navigators were among the most skilled seafarers in the world, and their traditional navigation methods are a testament to the ingenuity, resilience, and spiritual connection of the Māori people. These ancient seafaring skills, rooted in the Polynesian connection, allowed Māori ancestors to journey across vast distances, forging links between islands and creating a lasting cultural legacy. As the revival of traditional navigation continues in modern times, Māori navigators are not only reconnecting with their past but also ensuring that these sacred skills are passed on to future generations, keeping the spirit of Polynesian exploration alive for centuries to come.